These two Delaware bureaucrats decided they didn’t want Evalene Pyle’s story to end with a police report

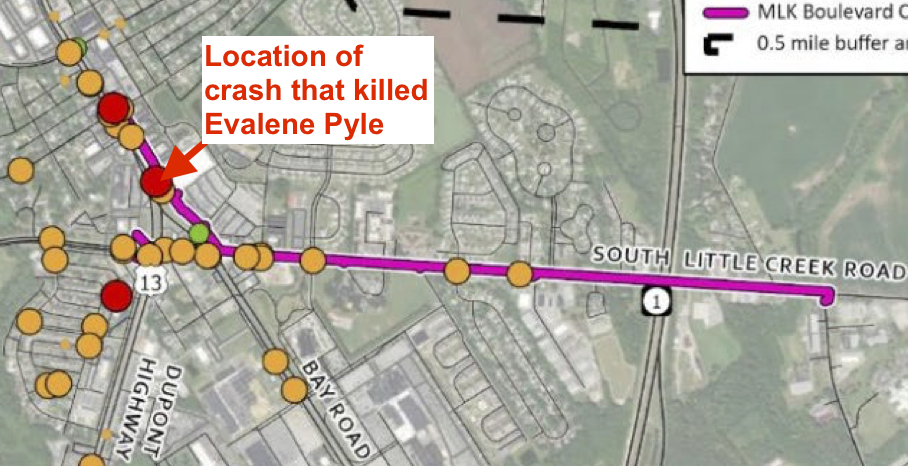

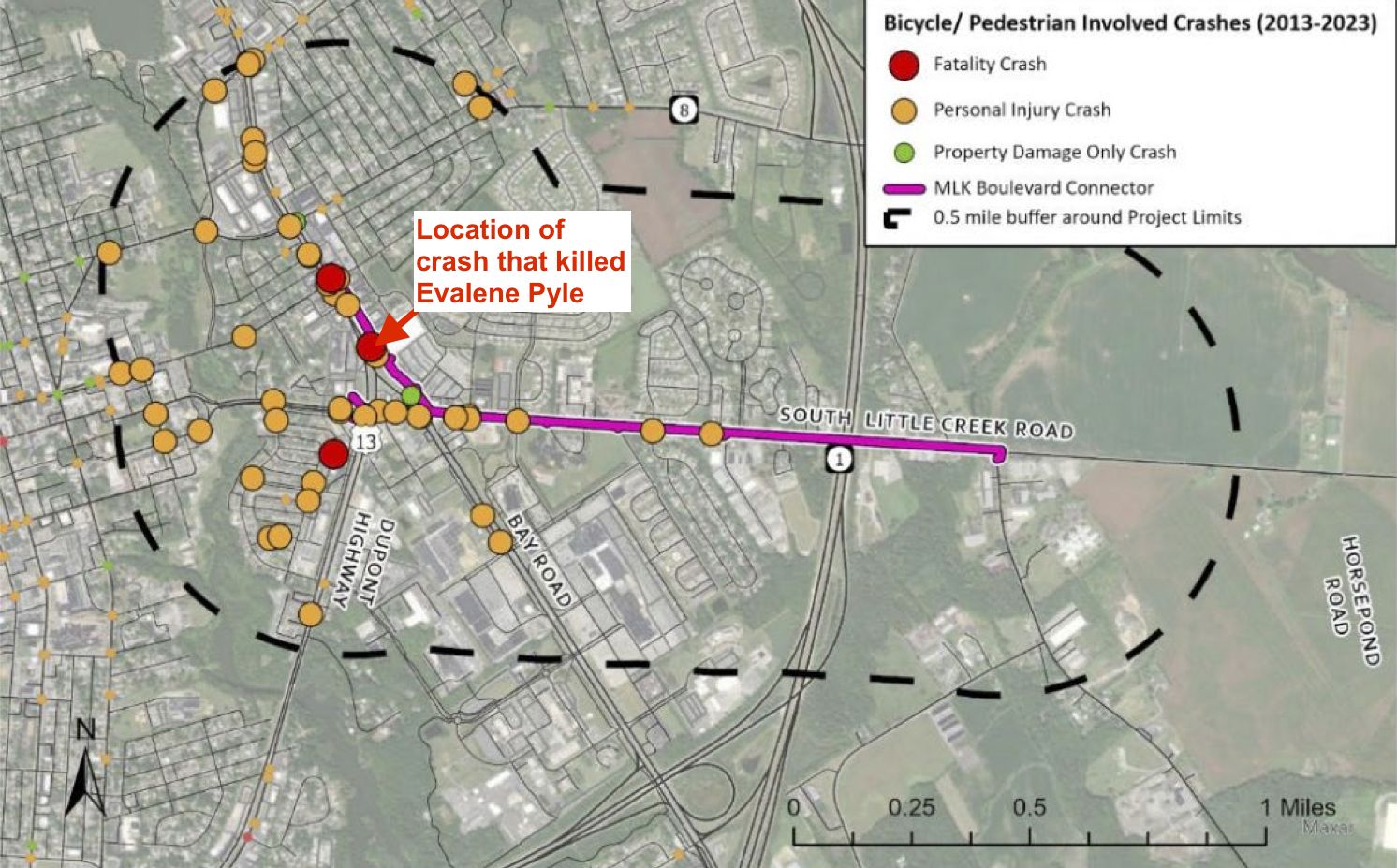

When Evalene Pyle was killed trying to cross US 13 on a bicycle in Dover in 2022, there was little news coverage beyond perfunctory repetitions of the police report. No TV reporter went to the scene. No candlelight vigil was held. Her death was never marked by any kind of physical memorial or public expressions of grief. She was one of a hundred and sixty five Delawareans who died in crashes in 2022, tying the all-time record for fatal crashes during a single year in Delaware. While in a perfect world we would like to see every traffic fatality result in action and systematic change, in reality it’s very unusual for any specific traffic fatality — no matter how horrifying — to lead directly to specific changes or projects intended to prevent similar crashes in the future. And so, normally, Evalene Pyle’s story would have simply ended with that barely noticed police report.

Bureaucrats

Maria Andaya and Paul Moser both work for DelDOT. We rely on them, and their many colleagues, to plan, design, build, and manage nearly all the streets, roads, and pathways that we use every day to get where we need to go. (More than 90% of all streets and roads in Delaware are owned and managed by DelDOT.) “Every day, regardless of the weather, you will see a steady stream of people walking or bicycling along the 1.2-mile stretch of South Little Creek Road [in Dover] to meet their daily needs or to get to work,” Andaya noted. “Many of them cross Bay Road and US 13, which are high-volume and high-speed arterials, creating dangerous conditions.” There wasn’t any money in DelDOT’s budget for Andaya or Moser to fix these dangerous conditions, but after the death of Evalene Pyle and on his own initiative, Moser developed the rudimentary first stage of a significant safety project that would include shared-use paths, crosswalks, curb ramps, pedestrian refuge islands, and median fencing. “The first concepts were designed,” said Moser, “but budget estimates were higher because of highway barriers, utilities and other issues.” In fact, the cost estimate Moser developed for this project exceeded $12 million dollars.

Rather than giving up at that discouraging number, Andaya and Moser decided instead to pile even more work on their plates by going through the very complicated process of applying for a federal grant. “Preparing a complex grant application requires significant time and effort, with no guarantee of success. But we decided to pursue this opportunity because of the tremendous need [in a] historically disadvantaged community with many residents unable to drive” said Andaya. Moser was more blunt: “Applying for the RAISE [Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity] grant [a discretionary federal transportation infrastructure funding program administered by the United States Department of Transportation] was a shot the dark.” The basic project description for the application they developed was 6 pages alone. The “merit criteria” documentation was 16 pages, the benefit-cost analysis was 21 pages, and there was a final 4 pages of appendices.

But there was one other thing that their application turned out to have in abundance: support from Delaware elected officials at every level. Lots and lots and lots of support. The mayor of Dover wrote to USDOT Secretary Buttigieg asking for his help to make walking and cycling safer in Dover. Governor Carney wrote a letter in support of the application on February 22, 2024. Finally, and perhaps most persuasively, Delaware’s entire federal delegation added their voices in unanimous support for DelDOT’s application.

Bike Delaware also wrote a letter of support to Secretary Buttigieg which noted that Americans often think of traffic deaths as an inevitable cost of “modern” mobility but pushed back against that idea by noting that countries like France or Germany suffer per capita less than a third of the traffic fatalities that Americans experience while a country like Norway has 80% fewer such fatalities per capita. The difference is not more careful people but rather decades of focused public investment in infrastructure.

DelDOT submitted the RAISE grant application on February 28. Through the rest of the Winter and all of Spring of this year, Andaya and Moser wondered whether all of their work would be for nothing.

USDOT received over $13 billion in requests for RAISE grant support. At the end of June it awarded $1.8 billion in grants, less than 15% of the total amount of support requested. Delaware received only a single RAISE grant: $12.25 million for Andaya and Moser’s MLK Boulevard Connector proposal.

Delaware’s entire congressional delegation celebrated the huge win.

“Since last year, we’ve started to see roadway fatalities decline in Delaware and across our nation after reaching a 40-year high,” said Senator Tom Carper, Chairman of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee. “This grant will make much-needed infrastructure improvements to protect all roadway users — whether they are traveling by foot, bike, or car.” Senator Chris Coons emphasized the benefits of the project. “These improvements will make Dover’s roadways safer and more convenient for pedestrians and bicyclists, and that’s always a wise investment.” And Representative Lisa Blunt Rochester said that the “grant…will mean a safer Dover for bikers and pedestrians.”

“Bureaucrat” is a double-edged word that over the years has acquired a number of negative connotations. If you google the word, the definition the internet offers up is “an official in a government department, in particular one perceived as being concerned with procedural correctness at the expense of people’s needs.” But the main reason that Evalene Pyle’s story did not just end with that police report is that a couple of DelDOT bureaucrats decided they didn’t want it to. And while everything they did was procedurally correct, they used those procedures in order to try to make infrastructure improvements that will save lives and prevent more tragic stories like Evalene Pyle’s.

“The least we can do“

Just a decade ago, $12 million would have been more money than Delaware had ever spent on a single bicycle/pedestrian infrastructure project. But even today in an era when DelDOT undertakes major projects like the Markell Trail and the Lewes-Georgetown Trail, $12 million is still a huge amount of money. But it’s actually just the beginning of the colossal amount of work we have in front of us to fix the ridiculously dangerous transportation system we have inherited from our predecessors, one that is deadly for drivers, deadly for kids, and really, really, really deadly for people who don’t own a car. Andaya says that no matter how difficult and expensive it will be to fix the infrastructure mistakes of the past, she and her DelDOT colleagues have a duty to pursue that work. For the people who are living every day with the consequences of the incredibly bad infrastructure decisions made in past decades — especially people like Evalene Pyle — “the least we can do is make it safer for them.”

If you are interested in learning more about this $12 million project in Dover, there will be a public workshop (hosted by DelDOT) on Tuesday, August 27 between 4 and 6 pm.