Safety First. And Congestion Reduction Last.

For the last two years that federal statistics are available (2012 and 2013), Delaware had the highest per capita pedestrian fatality rate in America.

As the Delaware Department of Transportation and the Council on Transportation revise the Department’s process about deciding which transportation projects should get built, it is a good time for a reminder about the differing magnitudes of the cost of congestion and the cost of crashes.

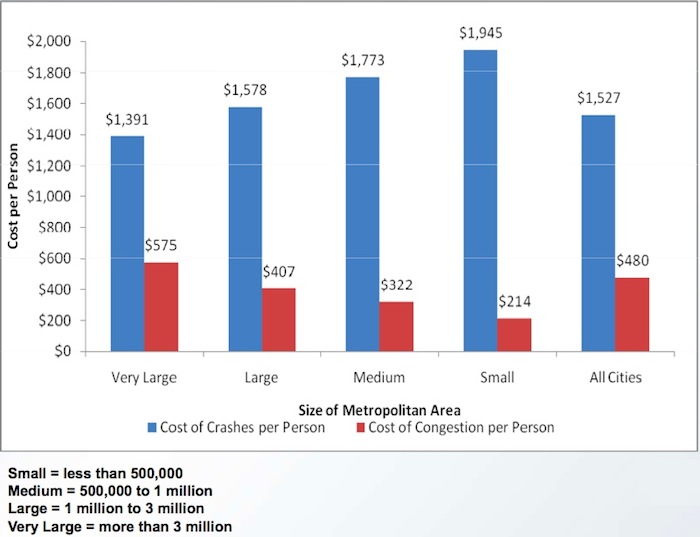

Researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology looked into the data in 2011 and quantified the (per capita) costs of both. The red bars are the cost of cashes and the blue bars are the cost of congestion:

Source: “Economic Cost of Traffic Crashes: Establishing a System Performance Measure for Safety” (Transportation Research Board)

The costs vary depending on whether you live in a big city or a smaller city.

America’s largest cities are both more congested and safer – from a traffic point of view – than smaller cities. But as you go to smaller cities (and then presumably to suburban and rural areas), the per capita cost of congestion goes down while the per capita cost of crashes rise. For small cities, the total cost of crashes is nearly 10 times more than the total cost of congestion.

(What is a “small” city by the way? The Georgia Tech study defines “small” as less than 500,000….Wilmington, Delaware’s largest city, has less than 80,000 people in it.)

For Delaware (with no big cities at all) the cost of crashes vastly outweigh the costs associated with congestion. And that does not even take into account another important issue: reducing congestion can actually reduce safety. This report from Portland Metro (2012) documents this phenomenon. The “KSI” (“killed or seriously injured”) crash rate in “uncongested” conditions was nearly 50% higher than when conditions were “congested” (page 33 of the report). The data reflect that reducing vehicle congestion by widening arterial roads is not an effective long term safety measure. The problems introduced due to widening are faster vehicle operating speeds, complicated lane transitions and more difficult multimodal crossings. Clearly, there are crashes in the periods where congestion exist, but it is not the majority of crashes because the transportation system offers significant exposure throughout the other 23 hours after the peak hour. (For example, in Delaware most fatal pedestrian crashes happen after the evening rush hour when there is little or no congestion.)

From a strict cost-benefit point-of-view that only compares the economic costs of congestion and safety, we need to prioritize safety. In the context of a fixed amount of funds for transportation improvement, that also means we need to de-prioritize projects that reduce congestion without a safety benefit (or worse, actually make deadly crashes more likely).

James Wilson is the executive director of Bike Delaware.

RELATED:

• Economic Cost of Traffic Crashes: Establishing a System Performance Measure for Safety (Transportation Research Board)

• Metro State of Safety Report

• News Journal: “Pedestrian, bicyclist deaths jump in 2012 traffic fatalities”

• Road Safety in Delaware: How We Can Reduce the Number of Dead Pedestrians

2 Responses

Good post!

If you want to see other states follow Delaware’s lead on Share The Road, please vote here:

http://www.bicycling.com/news/advocacy/vote-bicycling-people-s-choice-advocacy-award

Comments are closed.